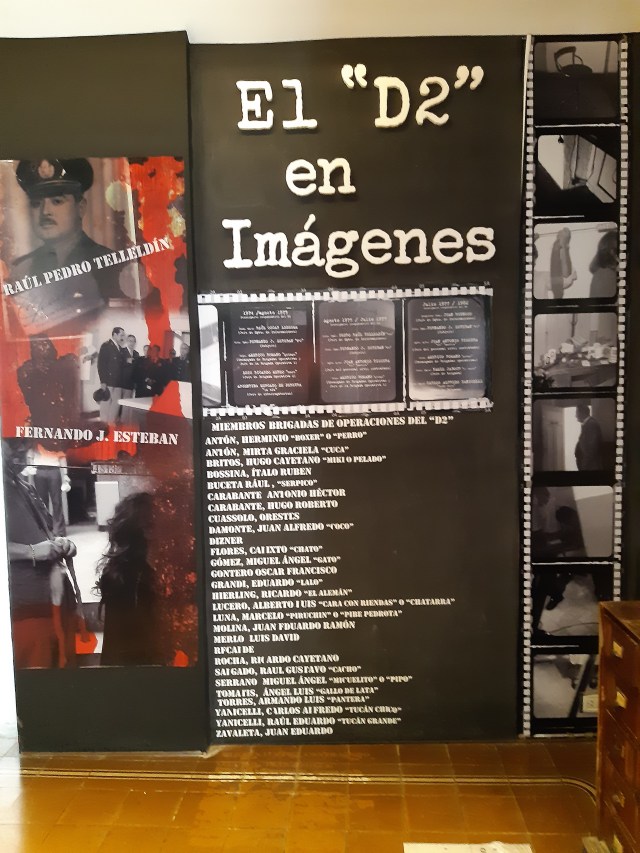

I have to write about this, much to my dismay. The atrocities that occurred during the Época de los desaparecidos (Dirty War) in Argentina, from 1974 – 1983. I innocently walked into the Museo de Sitio, a museum off a side street from the main square in Córdoba (Plaza San Martin), and was confronted with these dramatic reminders of the past. It was called D2, the place where dissidents were taken in, kept in cells (up to 40, in a very small space), and tortured, right there behind a church in the middle of the city.

It reminded me of the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh, which depicts the Vietnam war. Except this was the réál place, not a museum. Fortunately there were no horror torture pictures in this one, but enough other material to indicate the human suffering.

These are the faces (during their trial) of some of the leaders responsible for the capture, torture and disappearance of about 30 000 students, trade unionists, writers, jounalists, artists and left-wing activists, whether they were leftists or not. The different areas of the museum tell the sad tale of organisations and family members trying to come to terms with this violent history. Many photo albums of lost family members are on display, and one can only hope that the putting together of this material brought some therapeutic relief for surviving family members. Mass graves were only discovered 10 years ago, and teams of pathologists have been working through the bones, using DNA tests to identify victims and return the remains to the families concerned.

The courtyard of the prison. Each lightbulb represents a body that has been found, and as new ones are discovered, more bulbs are added:

¿Dónde están? (Where are They?) Parents asking questions.

A few days later when I passed the museum again, these pictures of some of the missing people were being displayed in the street.

The Pardon Laws that were passed in 1986, preventing further prosecution of the perpetrators, were repealed in 2003 under Nestor Kirchner, the president at that time. Investigations were re-opened and prosecutions resumed in 2010. Thus all is still very fresh in the minds of the people.

For me it had become personsal because a friend had told me that her husband had left university in Córdoba in those years, as he had feared for his life after his brother had disappeared. He never completed his studies, which permanently impacted the rest of his life in various ways. That is what they did: if a family member ‘disappeared’, other family members would be imprisoned and tortured for further information. So he saved himself by leaving university.

I looked up some of the history, and will just give a brief summary here.

The military had tried to stage coups in 1951 and 1955, finally succeeding in 1976 under the leadership of Jorge Rafael Videla, unseating Isabel Peron (not Eva Peron – Isabel was Juan Peron’s 3rd wife), who had been president for 2 years. She had already started a campaign against left-wing Peronists and political dissidents, signing documents that allowed the military to suppress any activities.

The junta called their operations the National Reorganization Process, which used the government’s military and security forces for repression. Together with the Alianza Anticommunist Argentina (AAA), which was under the rule of Jose Lopez Rega, the minister of Social Welfare, they proceeded with their reign of terror. People were drugged and pushed from planes naked and semiconscious, into the sea or rivers, or shot and buried in mass graves. A navy captain, Adolfo Scilingo, who had excecuted thousands of people, admitted during his trial that they had done worse things than the Nazi’s. There were 340 secret concentration camps spread over Argentina where prisoners that were not killed, were interned, interrogated and tortured.

All this was happening with the backing of a USA campaign, called Operation Condor. The latter was operational from 1968 to 1989, and was there to support the suppression of left wing activities in Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Brazil and Bolivia. Between 60 000 to 80 000 people were killed during that time, and a further 400 000 were imprisoned. It finally came to an end after the fall of the Berlin wall.

In 1983, after the defeat in the Falklands, Argentina had a democratic election and under the new president, Raúl Alfonsín, investigations regarding the crimes were started. Testimonies from witnesses were used to develop cases against the offenders, and in 1985 the Trial of Juntas began. Over 300 were prosecuted and many officers were charged, convicted and sentenced. In 1986 the military started protest actions against the trials, with them enforcing the Ley de Punto Final (Full Stop Law), which prevented further prosecutions. This was only repealed in 2003, as I mentioned earlier, and the process of bringing the guilty to trial could resume.

I walked out of the museum feeling emotionally drained. I looked at the people in the street, wondering how they could be so ‘normal’, how they deal with such a sad history. And I thought of Apartheid, and how we deal with our own terrible past. And I realised that life goes on, no matter what, and we as humans have the ability to reflect on and learn from the past, hopefully using it to create a better future.

Tomorrow I will write about the other experiences here in Córdoba this past week, much more fun. Here is a sample (Carmen, at Teatro Real, and a train ride):

Dit is hartseer geskiedenis waarvan ons niks weet nie! So het elke land seker maar sy eie vreeslike stories uit die verlede en nie net SA nie🙈

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ja né, so is dit. Ek sukkel altyd om te verstaan hoe mense so wreed met ander mense kan wees.

LikeLike